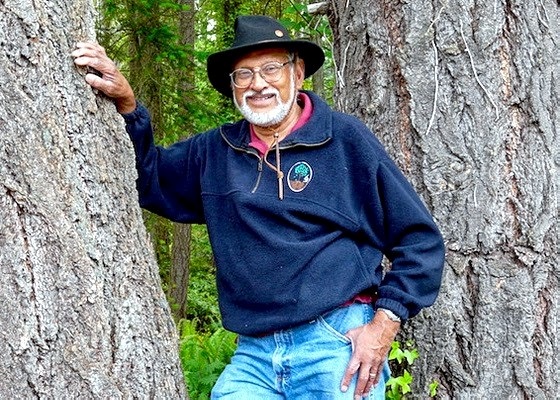

Dr Olaf Ribeiro thought he would spend the rest of his life in Britain when he got word from his mother that Kenya was preparing for independence and was looking for citizens to train to take over the agriculture in the country.

FAMED GRANDFATHER

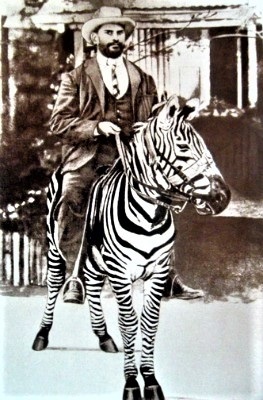

Dr Olaf Ribeiro is the grandson of the pioneer Kenyan-Goan doctor Rosendo Ribeiro, who was conferred an OBE by Britain in 1932 and the award of Commander of The Order of Benemerencia from the Portuguese government in 1947.

Dr Rosendo, who was born in Porvorim in 1870 and moved to Mombasa-Kenya to work as a doctor in 1899, discovered a cure for malaria which he sold to the British in exchange for land. The British went on to profit handsomely from this transaction. He also discovered the Bubonic plague and developed a cure for it. He was also responsible for being a founding member of the Dr Ribeiro Goan School in Nairobi, many of whose alumni went on to become outstanding members of the community. Dr Rosendo died in 1951, aged 80. His remains are interred at the City Park cemetery in Parklands, Nairobi.

Dr Rosendo was famous for riding a zebra on his visits to patients. He later sold the animal to the Bombay Zoo.

RETURN TO KENYA

Recalls Dr Olaf Ribeiro, “I flew home to Kenya, interviewed with the Ministry of Agriculture and in short order was given a full scholarship on my way to Egerton College, Njoro located 120 miles from Nairobi in what was known as the White Highlands of Kenya. It was to be a two-year diploma course. I arrived to find an interesting mix of students.”

“All of us had previously been working in different jobs including Customs Officers, Desk Clerks and Accountants. Very few of us had any idea of agriculture! This was to be a grand experiment in getting Kenya ready for independence. The college was a previously all-white college set up to train the sons of white farmers to farm. The instructors came from Britain, the US (on a foreign aid programme), an Australian and a Dane.”

“Students were British sons of local farmers, Indians (Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, and Goans), natives from various tribes (some traditionally hostile to each other!) and even an Italian student, Luigi, whose parents were farming in Somalia.”

“We all shared the same dormitories. Amazingly, there were very few skirmishes although there were occasional skirmishes with the white British kids who greatly resented us “coloureds” in what was formerly a white domain. In fact, the manager of the estate Major Thornton, could not handle the fact that the place now had “coloured” students on the premises. He settled the issue by committing suicide with a shotgun to his head.”

PRACTICAL EDUCATION

Dr Olaf Ribeiro said the farm consisted of both animal husbandry and agronomy units.

“It was the most complete education that anyone could ask for in agriculture and animal farming, including wheat, barley, potatoes, and pyrethrum as well as milking cows, castrating piglets, shearing sheep, treating sick animals and learning to drive tractors and combine harvesters.”

“We also learnt how to slaughter animals for our meals and to use the remains to study anatomy. I had my fair share of mishaps from shearing off the teats of a sheep to killing another by pressing too hard on the animal’s neck as I held it between my legs to shear it!”

In time, Dr Olaf got to manage the agronomy farm when the farm manager left for overseas leave to Britain.

“These were the early days of Uhuru and much of the colonial influence was still alive and well. It was a pretty swell life, the students had a bar (which they welcomed with Kenyan joy), played hockey and soccer and competed with teams from as far as Nairobi, Mombasa and Kampala.

Life was bliss, especially when the pitch-black Kenyan night delivered a super-scope canvas full of stars, sometimes a comet or two and regular shooting stars. It was a kind of heaven,” said Dr Olaf.

[The writer is a Kenyan-born journalist, who worked for the Nation Media Group in the 1960s and left as a chief reporter. He now lives in Australia.]